Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Last Front (2024) Film Review

The Last Front

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

When we talk or make art about European wars, Belgium has a tendency to be neglected. Its own aggressive incursions mostly focused on civilian populations on other continents. For most of history it wasn’t worth occupying for long periods, because it was impossible to defend. It was, however, marched through by practically everyone, en route to more strategically valuable conquests. An uneasy peace was maintained at these times by an honour code which it was in everyone’s interests to follow. Soldiers would take only what they needed, they would mostly leave civilians unmolested, and in return they wouldn’t have to worry about violent resistance. When this went wrong, things could get ugly very fast.

The 20th Century, with its new weaponry and its obsessive approach to controlling even tiny patches of land, saw the stakes raised. When Germany asked for permission to pass through, Belgium said no, and a formal invasion, leading to several bloody sieges, ensued. The violence most centred on cities, however, with villagers hoping that they could go about their business without too much trouble. The problem was that wherever you have groups of nervous, poorly trained young men, a long way from home and its familiar rules, in a land where they have been warned that they are under threat of violence, trouble can happen all too easily.

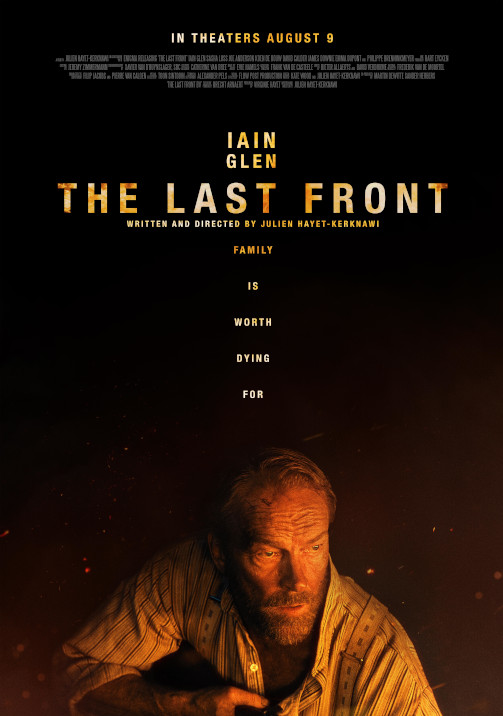

The dizzying contrast between day to day life and the chaos of war is central to this violent yet meditative film by Julien Hayet-Kerknawi. In its opening scenes, the villagers we meet have concerns which bother them deeply but which will come to seem trivial. At the heart of this is the romance between farmer’s son Adrien (James Downie) and well-to-do doctors’ daughter Louise (Sasha Luss). Both sets of parents feel it’s inappropriate but seem unable to talk them out of it. We spend most of our time with the farming family, as Adrien’s father Leonard (Iain Glen) will come to the fore when a violent incident on his property throws the delicate balance between locals and invaders out of kilter.

Those invaders are a small but well armed unit led by Maximilian Von Rauch (Philippe Brenninkmeyer), a man with a strict code of honour. Aware that the unit is vulnerable, he wants to pass through with as little fuss as possible – but whilst he commands most of his men effectively, that doesn’t extend to his hotheaded son, Laurentz (Joe Anderson). With a poor understanding of the mechanics of power and a desperate urge to prove himself, the young man thinks that he can solve everything with violence. When he crosses Leonard, he will learn where that leads.

This isn’t quite the standard gung-ho actioner. Leonard is a man who would rather not fight. His priority is getting people to safety – not just his own family members, but the neighbours he has known for his whole life. There’s no suggestion that he has military training, but like a lot of farmers, he has had to learn how to shoot, and he’s physically strong. When he realises that the Germans could well work their way through the town killing everyone they find, he prepares to make a desperate break across the fields and through the forest to the French border – but in order to stand a chance of success, he will first need to take something that the Germans have.

Tangled up with the fleeing people’s fear and desperation is an experience common to refugees but rarely addressed in cinema: a deep love of the land being left behind, an appreciation of its beauty and a sorrow upon parting. This is expressed most directly by Louise, and the presence of this young woman gazing around dreamily at the landscape as she twists her golden hair is something of a cliché, albeit one we might not expect to encounter in this context. Glen also gets his moments, however, and these are the ones that provide him with the most to do as an actor.

Hayet-Kerknawi has cast the small roles well and the film remains involving throughout. At a thematic level, there’s nothing new here, but the story is well told and the locations are well used, giving it a specificity that helps a good deal. It speaks not only to the Belgian experience but to that of rural people everywhere whose stories get lost in the grand narratives.

Reviewed on: 31 Oct 2024